Interview with Don Tendon

Add to collection

You do not have access to any existing collections. You may create a new collection.

Downloadable Content

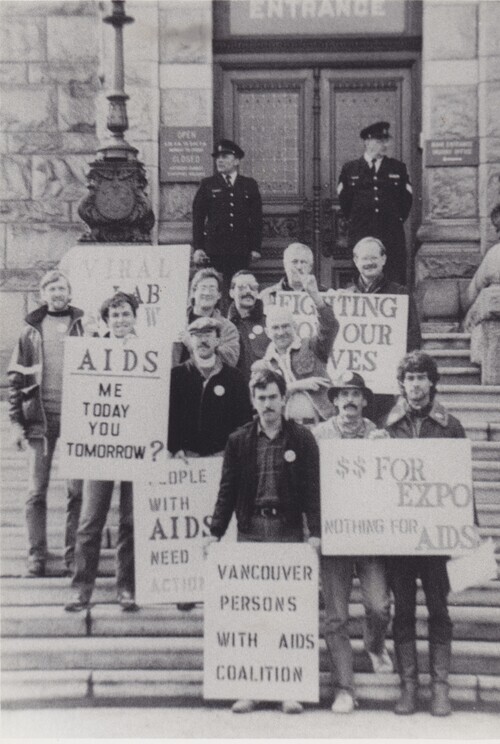

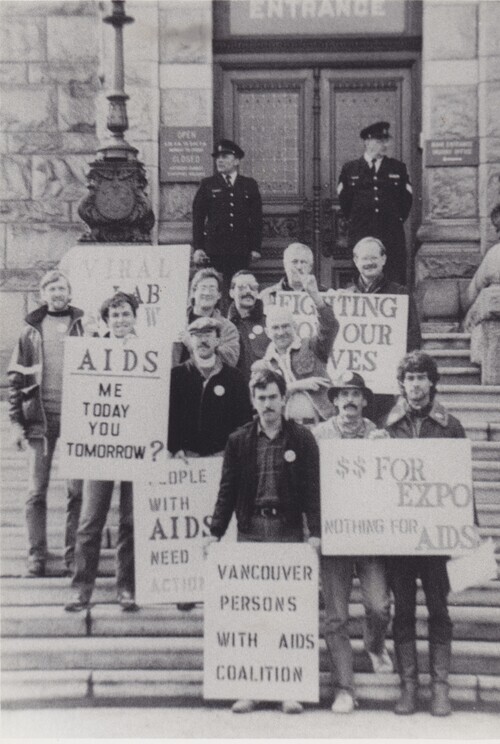

19-05-06-DT.docx “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 1 “HIV in My Day” – Interview 86 May 6, 2019 Interviewee: Don Tenden (DT); Interviewer: Ben Klassen (BK) Ben Klassen: Great, thanks for being here, Don, and agreeing to share your story with me today. Could you tell me how you first got involved with the gay community or started to engage in gay life? Don Tenden: I was living in Port Colborne, Ontario. I was – I have known I was gay since I was in kindergarten – or different, I didn’t know I was gay, and eventually people started asking, “Why isn’t Don interested in girls?” So, I went out with a girl for a year, and that wasn’t working, and I knew I was gay, and so after, I kind of burst out of the closet and moved across the country – “I’m gay and I’m leaving. Bye.” And when I lived here, somebody that I had met back east, he used to live back there, but he had moved here. He had arranged for an apartment for me, and it was in the stack o’ fags, 1150 Burnaby Street. You never heard of that? BK: Maybe I have. DT: It was 1150 Burnaby street, primarily all gay. Yeah. And I come from a small town, there was no gay scene at all. My first job was in Celebrities, so I kind of bang, I was in it. That is how I got involved. BK: That is quite the dramatic transition. DT: Yeah from a town of 15,000 to a community of 15,000. BK: What was the community like in those early years? DT: I was just amazed when I first got here – oh my god, I couldn’t believe it. It was a lot more concentrated in the West End because of security type things. There were people getting beat up and homosexuality wasn’t quite as accepted. BK: There was a lot of animosity toward the gay community back then. DT: Yeah, the testosterone-filled rednecks coming down on the weekends looking for someone to beat up. Nowadays, there are gays all over the Lower Mainland. Back then it was, we stayed in the West End, Commercial and the West End, and that was pretty much it. There was many out and about. What was it like? It was sad. People were dying, they were visibly dying all over the place. Used to pick up The West Ender and open up right to the proud lives and see who had died. Dr. Peter was doing his special, so every week you would see him progress. It was really sad because there was a lot of stigma going with it back then. Reagan had banned entry into the US for anyone that was HIV and it wasn’t until Obama’s second term that it got lifted. I had a job that kept sending me down there, and I kept telling them, “I could get turned back, just so you know” – that was in Tennessee. I will start with being back in Ontario first. Dysfunctional family. I was smoking back then, I was thirteen, I was my mom’s drinking partner at fifteen. I “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 2 was just like, this is a really dysfunctional household, just a mess. I won 150,000 dollars on Lotto 6/49 at twenty, put myself through college for a couple years. I was working nights, cleanup at a meat processing plant at the time. Like I said, I had experimented with a couple guys in high school, but I hadn’t been in a relationship or anything. I fell in with this wrong group of people, who let me be gay with them if I got them high on coke, and I got introduced to coke. The first two years, I did great, and the last year when I got into coke, I ended up leaving Ontario 80,000 dollars in debt, because once you got money, they keep giving you credit cards. I fled debtors and just left. I moved here, I moved into 1130 Burnaby Street. My first job was at Celebrities, working. Somebody broke into my apartment and stole everything that I owned right down to the pillow cases on my bed. Basically, when I came here, and it cost me, I shipped all my stuff out and it was a lot of good stuff. I was one of the few people who had a computer in those days, and it was all gone. I had no insurance, and no one saw a thing, so basically, I was starting from scratch. It cost me basically everything I had to move out here, everything I could muster up on credit to move out here and come up with rent and what have you. Celebrities at the time was [Studio] 54, cocaine was going through that place by the shovelful at that time. So, I maintained that coke issue for a while. I met the first guy I ever dated seriously – he had fallen in the garbage can, a 45-gallon garbage can one night at Celebrities ass-first and he was stuck, so I got him out of there and I dated him. I can pick ‘em. It turned out he was positive – he knew he was and he infected me and never warned me or anything, so the first guy I ever dated infected me. I have been positive my entire gay sexual adult life, more than half my life now. I am fifty-three and have been positive thirty-one years. Where to go? So, I saw that he was getting sick – he never admitted it to me, but I saw that he was getting sick. I had moved to Surrey at that point, I had moved in with him in Surrey, and there was two reasons for that: number one, I couldn’t afford it here living on a bus boy’s salary, and number two, I was really afraid I was going to pick up a West End effeminate swish and have to go home one day and be an embarrassment to my family, and I was horrified about that. So, I moved to Surrey, and that was a mistake – didn’t take me long to realize I didn’t move across this country to be in Surrey. I moved in with him and I saw him getting sick. I could tell he was getting sick – you saw people all the time getting sick. You would see their partners pushing them around getting sicker and sicker and sicker, and they would die, and then a couple months later, you would see the partner died, and they would go one after the other like that. People that were sick were very visibly sick, the Kaposi’s and wasting and frail – they were very sick. We both went and got tested at VGH, and they didn’t go get tested, he didn’t want to. And we got the day to get our results and we went in at the same time – we got our test done at the same time, but on the results, they made a mistake on my date to get my results and they put it on the day after I was supposed to go, so he got his results the day before I did. We were supposed to get them at the same time. He tested positive, so I kind of knew I was positive the day before, so I went in and sure enough, I was positive. And you kind of go into shock, you just keep going – you are twenty-three years old and positive, and I am coming from a small town. AIDS was something you only heard of on TV. At VGH, the woman who broke it to us was very nice, very sweet. Basically, “You’ve got AIDS. Here is a cassette tape for you. Go.” That was it, we got a cassette tape – I never listened to it, it seemed ridiculous. There was no offer for support or “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 3 anything. I got referred to [doctor’s name], who was one of the HIV – there was only three or four HIV doctors back then. I got assigned to [name], who initially was great. Over the years, I ended up having some problems with him, but initially it was fine. BK: When you were diagnosed, the doctor at that point said get your affairs in order? DT: Basically. At VGH, they didn’t say anything, they referred me to [doctor’s name]. At first, it took me three months to get in there. You kind of go into shock and it is like regardless of this news and how devastating it is, you have to pay your rent you have to keep going. You do go into shock, you go through the motions every day, but you aren’t really processing the emotions, you are going through the motions. I would say it was six months before I snapped out of it. When I did get in to see [name], I was basically told one to three years, get my affairs in order. It was hinted that I would be luckier if it was one year because people were suffering – when you died, you suffered, you didn’t go graceful. Back then, there was kind of an underground thing where a lot of patients got a lot of morphine backed up, certain doctors would prescribe them morphine so they would have an out when they needed to. Over the years, I amassed a bunch of morphine as people died, but I have gotten rid of that – it was a different time. People were dropping dead all over the place. I lost a lot of people. So, I don’t know, moved back down to Vancouver after a year in Surrey. I still – the guy that infected me, I was friends with him for another ten years, I didn’t know anyone else. On top of that, testing positive and getting my whole place ripped off, my mom died six months after I got here, and we were really close, and I didn’t get to make it back before she went, so that was hard too. I look back at that period of my life and say if I can make it through that, I can make it through anything. If it doesn’t kill you, it will make you stronger. I have been very lucky. I have worked for seventeen years, I have always worked, I never collected EI. I collected one welfare cheque while I was waiting for EI to kick in, but by the time that was supposed to kick in, I had another job, so I have always worked. I worked for seventeen, eighteen years before I ended up going on disability, and yeah, I didn’t let it get to me. My mom had suffered her own cancer for seven years, she had double mastectomy, I come from a line of very heavy smokers, so she never let on that it was a problem, she never complained to anybody, she had a good attitude to the whole thing, she never complained, never let on to anybody, and I wanted to be the same. I took her as a role model – I was going to be the same. So, that is what I did. I didn’t let it bother me, I didn’t let it run my life, it was just a part of my life, but I wasn’t going to let it be the entire focus of my life. The meds back in those days were horrible. They were very strong, we were severely overdosed, because they didn’t know doses or anything, and at one point, it was either 3TC or d4T, it was one of the two, because I was doing them both, everyone was doing this. You would walk around and you would just crap your pants - no notice, nothing – you would just crap your pants. I made a choice, I am not going to live the last days of my life like that, so I went of my meds. Done that a few times over the years, I get shit for it. They don’t like it, but you know what, I know when I need to take a break. I could tell when – yeah, we were really overdosed. There was a point I was turning yellow, my eyes were yellow, my skin was yellow, and I gotta go off these meds for a while and I did. I found that I could go off for a few years at a time before my numbers would start to go into the danger zone again. I respond very well to meds but I have never taken the full “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 4 dose that they prescribe. I do now because they prescribe a reasonable amount. But they always had this double dose, at least, I used to take like eight ritonavir a day, I would take one. I was dating a guy that was twenty-eight – I was thirty-three – and he died. And he had this cat, this cat hated me. We would be sitting there watching a movie on the couch and the cat would sneak up behind me and give me a swat, and I would be bleeding all over the place – she hated me. When he died, she hated everybody, it wasn’t just me. So when he died, I knew if I didn’t take her, she would be put down and I couldn’t handle that, so I took her home and I gave her space. I kept her litter clean and her food – I knew what kind of food she wanted, and I just “It is your place, do whatever you want.” I didn’t force myself on her or anything, I just gave her the run of the place. And for two weeks, she didn’t talk to me at all, she just walked by me and hissed and just walk by me, and then one morning, and I woke up, and she was like a puppy, she couldn’t get close enough to me. And I had her for another thirteen years, and losing her was probably harder than losing any person cause she was with me a long time through a lot of people, and she represented [partner’s name], so… BK: Were you hearing about HIV when you were living in Ontario? DT: On the news you would hear about it, like when Liberace died and everyone knew it was him, Rock Hudson. Reagan had banned us from entering the US. It was basically, it was for gay - for gays, hookers, and drug addicts, basically, so if you had HIV you were deemed dirty. And even to this day, clean people refer to themselves as being “clean.” BK: How were you responding to some of that early information? DT: I kept myself quite self-medicated for a lot of years – a lot of people did. I don’t advocate this, but I somehow think that it kept me alive for some reason because it raises your metabolism, your whole system, right? Yeah, I just – I drank like a fish, I didn’t have a vegetable for years, I didn’t take care of myself at all, I did everything wrong, I did everything I wasn’t supposed to do, and I just kept going. There were points where I was – I have never attempted suicide but there were times I went off my meds because I just didn’t have it in me to fight anymore, ‘cause it can be a straight uphill climb all the time. The loss is unrelenting, it doesn’t stop. It still doesn’t. Like, even plagues don’t last this long, usually they are done in ten years. This has gone on over thirty already, and people are still dying. They are attributing it to different things now – they are still dying due to medication and disease, That makes me very sad that nowadays that it is being touted as nothing, it is easily treatable. I don’t know but it doesn’t seem to have – because it isn’t visible, you don’t see people being sick anymore. You used to see them everywhere, people were covered in Kaposi’s. You don’t see that anymore, you don’t see people wasting anymore. So, I think people think it is nothing anymore, but I know damn well that these pills are so hard on the organs. I broke my back and I couldn’t take pain killers because my liver and kidneys were already taxed from the HIV meds. I couldn’t add pain killers on top of that because they are processed through there too. Yeah, it has been hard. Doctors have egos unfortunately. When I ended up getting hospitalized the first time, when I went on disability, I had PCP pneumonia which is what used to kill everyone, and my doctor – I saw Julio Montaner for the first time, and I didn’t care for him at all. He was very rude, I felt like a lab rat with him, but my doctor seemed to have a jealousy issue “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 5 with me seeing with him and I got stuck in the middle of this weird – I didn’t know what to say, and it is like… But because I needed him to fill out my paperwork for my disability, it became clear with who I had to side with and who I had to walk away from, but it was kind of awkward there for a little while. Doctors, they don’t think – they think you are stupid if you don’t have letters after your name, they think you are stupid. I have a good doctor now – I like her, but I wasn’t impressed with them. I was at the beginning, but he didn’t really listen to me. I said – when I wanted to try to quit smoking, he went, “That isn’t going to be what kills you.” Just a few things like that. I complained to him about depression a couple of times and he told me, “Well, if you can’t pick up a self-help book, what am I supposed to do?” I’m like, okay. Generally, I find the care here excellent – those are the exceptions, not the rule, but there have been a few times when I have gotten really discouraged. I haven’t always adhered to my medication regimen the way they want you to, but I have always been honest about it, because I am part of a study group. So, I always sat there, listen to them denigrate me and berate me and treat me like a kindergartner, so I would sit there and do my interviews with a pharmacist and threaten to cut me off pills and everything. I am being honest, a lot of people weren’t taking their pills and were going there and lying, and so I didn’t want to sit there and take this shit, but I knew these were important – we were part of studies, so we were part of human trials, so I understood that. So, I sat there and ate it for years – being honest with you, stop yelling at me, and I know and don’t tell me one more time how important it is because I have heard it for thirty years. BK: That seems like a mixed bag of experiences in terms of the medical system and HIV. DT: About ten years ago now, I had a bunch of disappointing things happen to me. My doctor, [name], kind of let me go because I wasn’t following his instructions, so he just dismissed me after being his patient for twenty-five years, so it is like, okay, fine. And then I was volunteering at PWA and ended up at one of the retreats – and this can’t go on the report. BK: Should I turn this off for a sec? [Recording stopped] DT: So, I had a run-in with my doctor, I had a run-in with a friend – someone who just wasn’t who I thought he was. I thought he was more than – I thought he had more character than what he did. I had an issue with PWA, and I ended up handing in my membership there. And then I went to the pharmacy over here at St. Paul’s to pick up my meds one day, and I had been off my meds for a few years, but I’d been back on them and I was undetectable, and I’ve been going there for like twenty-five years – they know me there, right? So, I had gotten – the previous two visits there, I had gotten three months at a time, and I got this little twenty year old-ish, give or take, young upstart pharmacist with a god complex or whatever, and he was only going to give me one month worth of meds. And I said, “No, you can give me three months. My last visit I got three months,” because I did my three consecutive undetectables. With one undetectable and then two undetectables, I had gotten three months at a time. So, this little twerp – I was burying people before he was born – just a little snot-nose, “I can’t give you three months. We’re not supposed to.” And I said, “Yes, you can,” and I ended up having this little fight with him, kind of “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 6 holding back tears because it was just a rough period. Finally got him to give me three months, and the offices over there are just little closet-sized rooms, so I had gotten him to give me three months. I stand up and I started walking out of the room, and with my back to him, he says, “It would just be so much easier for everybody involved if you just took your pills the way you’re supposed to.” And I just, for the first time in my life, I pictured myself turning around, picking up a chair, and cracking him across the head. It’s like, are you fucking kidding me? And that was my breaking point – I was like, I can’t do this anymore, and went off my meds for five years. He was the last straw. And I ended up in St. Paul’s in 10C for three and a half weeks with an MRSA infection that almost took me out. My T-cell count was down to thirty. When I went into the emerg, I had a picture of my mother to put on my nightstand, and I basically told them I’m ready to go, just make me comfortable. Like, I was done, because I was done – it had been an uphill fight for a long time. They saved my life and I got a new really nice doctor there at IDC who I really like. She’s been wonderful – she actually listens to you and she respects me. She’s put me on a new program now that I only have to get my bloodwork done every six months, I don’t have to do sit-down appointments with the pharmacy anymore – I just call them, say I’m coming in to pick them up – and I only have to see her every six months now. So, kind of from thirty years of every few months or minimally, to now every six months and no pharmacy visits. So yeah, I like her. She respects me. The toll on my body, the toll on my health being on these meds and HIV for a lot of years is not good. I’ve got bad osteoporosis – some of it’s Truvada, some of it’s osteoporosis, some of it’s self-medicating – but I broke my back about five, six years ago now. I broke it in three places, and I lost four inches off my height. That was just after I had gotten out of the hospital, so that kind of sucked. [Laughs] And then they took me off Truvada and put me on a new drug, Descovy, and that kind of knocked my immune system back, and I got shingles in my eye. But I made it through that. Again, too stupid to lay down and go to sleep. For like a year, I had to use a walker – well, for a year, I had to get my groceries delivered, I couldn’t even take my garbage downstairs, had to get help with everything. And then I graduated to using a walker, which is really humiliating, kind of a kick in the nuts, and now I can walk with a cane and I’m getting better. I can walk to the store and back without it. But it’s been rough. Yeah. The medication is not always easy to take. I go through these periods where I want to take my pills, I lay them out, and they sit and sit there, and I just don’t take them. It’s not like a conscious decision, it’s like visceral – it’s almost like I can tell I’m getting poisoned by them again, like I need to take a break or I’m taking too much. Like I said, with these new medications, I’ve been okay lately, but over the years, yeah, it’s not like I choose not to take my pills, it’s just like it’s chosen for me. It’s not a conscious decision, I just can’t seem to stomach them. That’s caused me a lot of grief over the years dealing with doctors and pharmacy and whatever, but I’m still here, and people that took all the pills they were supposed to all died. I knew when I needed to take a break. Doctors think they know better than you and look at the numbers and what have you, but I can tell when I’m feeling good and I can tell when I’m feeling bad. BK: You’re an expert on your own health. “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 7 DT: You know when you’re feeling good, you know when you’re sickly. I once had the first signs of Kaposi’s, but they cleared up, except I have dental issues because my gums are receding and all my teeth have fallen out, and now my jaw bones and whatever that’s called – my jaw, the bones are shifting and moving, so I’m getting new dentures done up. That’s a big process. Okay, the financial aspect of this, there’s a big one. First of all, when you’re told you’re going to die, you don’t exactly plan for the future, right? First of all, I came here avoiding creditors, and coming here and getting these crap, minimum wage basically jobs, it was hard. I ended up working at the – it’s almost gone now – the Sheraton Landmark, then the Empire Landmark, and now it’s gone, torn down on Robson St. I worked in Cloud Nine for seven years, my last year there as the restaurant manager, and the same year that the owner of all the Sheratons in Vancouver went bankrupt, so Pricewaterhouse came in and took over and fired all the management. So, I ended up – I entered an ad in the paper for Squirrel Systems, which is a restaurant touch-screen system, because I had used it in the hotel, and they were looking for people. So, I got hired there right away – like I said, I’m always good at finding another job right away, I don’t just sit there. So, I got hired by them, I was there ten years. I worked five years on the end of an 800 line, and then I moved to quality assurance, research, and development, and then I became kind of – they used to call me Obi-Don because I was there long enough that I knew how it operated backwards, and I was meeting programmers, and I was doing clients because I knew all the bugs and what have you. They moved me into a position where I became – I was dealing with their hostile corporate clients, because we were late putting out software and it was bad when we did put it out – it was like really business-critical bad, like it would affect their business, like credit cards getting double charged, or in the middle of a dinner rush, their system would be down sort of thing – it was a nightmare. So, they kind of kept sending me to these hostile clients as their sacrificial lamb. Being a gay guy, they were sending me to Nashville, Tennessee just when Canada wasn’t supporting Bush when they were attacking Iraq. So, they sent me to two major corporate clients there, and between the two, they’re basically compounds – these restaurant head offices are like compounds, there’s everything – there’s shipping trucks, there’s everything. Between these two compounds there was an armoury. [Laughs] It was in Nashville, Tennessee and it was scary there – they just live and breathe Fox News. They’re horribly racist, they’re just – yeah, it’s a scary place to go at the best of times, and my job was sending me there. Because I was working in software development and I’m not sales, I’m not going to blow smoke up their ass, and I’ve worked in hotels and I’ve worked in restaurants, I know what business critical is like and I know what it’s like when your system goes down. So, I went there and I was completely honest with them, and they loved me, and I saved these accounts, and they were multi-million dollar accounts. When I got back from an eight-week trip, I got written up because I was being too nice to them and telling them stuff that I shouldn’t have been telling them. It was just like, things were getting stressful and what have you, and it was horrible – it was a horrible, stressful position. I wasn’t being fairly compensated at all. I got PCP pneumonia and got put in the hospital, and even that, I had to fight. I wasn’t ready to go in the hospital, I wasn’t like – my work has always been really important to who I am. So yeah, I got basically put into a quarantine room basically for a week – they put on level nine beekeeper suits to come in and see me, because they didn’t know what I had. And then when I had PCP pneumonia, which was an AIDS defining illness back in the day, I was told to go on disability, because if I go back, I’m done, “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 8 basically. It took a long time to accept that, and the HR person at the company I was working with, Squirrel, didn’t know what he was doing, and I ended up going almost three months without a paycheck, because you have to go to short-term and then you go to long-term, you go through your EI and all this stuff. He didn’t know what he was doing, and I went like two-and-a- half months without a paycheck. I was almost evicted. Eventually I got my retro for that, but I went to earning like 66% of my usual wage, and that was in 2006. I have private long-term disability insurance through Blue Cross – it was deducted off of my paycheck every week, and that was assessed in 2006 and it hasn’t gone up since, so basically every year, I make less and less money, because I collect the Blue Cross and then CPP disability. I have no provincial coverage whatsoever, which kind of sucks because I’ve got no dental, no optical, no anything like that – no prescription. And I’m making the same as I was making in 2006, barring the small increase of CPP. So, it’s hard. Everything is just getting more and more expensive here, and I’m past the point in my life where I can do a roommate again – I don’t want to do a roommate. Yeah, so I’m kind of at my end. I’ve applied for subsidized housing, but I never hear back – I don’t know why. It’s one of those things. I’m not there pounding on the door every day, I guess. So yeah, it’s been rough. For the last few years, basically, I pick and choose which prescriptions I can fill – I don’t fill them all. Yeah, it’s how I live now. It’s hard to take. BK: So, that’s a big present-day challenge. DT: Yeah, because this long-term disability insurance turned out to just be horrible. It’s just cash, it’s got no benefits whatsoever, and it hasn’t gone up since 2006. Like, what the hell? It’s a really bad policy. BK: Clearly, if you were talking to policymakers today around this particular issue, that would be one area that would need to change. DT: Yeah. Well, at least the employers, the plan they’re putting their employees on – don’t get the cheapest one available. Granted, I keep thinking I’m going to die, so I’ve been on disability now for thirteen years, and I never expected in my life I’d be on that – thirteen, fourteen years. Yeah, but I’m not even eligible for a transit pass, or no dental, no nothing, so it’s tough. And rent in Vancouver is retarded [sic]. BK: It’s crazy. DT: Yeah. So, how do you like me so far? BK: It’s good for us to hear this because we realize that long-term survivors are dealing with a particular set of challenges that folks who are newly diagnosed today are not dealing with, and so this is a very valuable part of the project actually. DT: It really makes me sad to see the youth these days not having seen what it was like during the epidemic, not seeing the suffering, not seeing the people dying. Like, people are still dying, but it’s just in the paper and it’s not attributed to HIV anymore, because they’ll die of kidney “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 9 failure, liver failure, heart attack, or stroke, but you know, it’s still due to HIV and meds – we can pretty much say for certain. It’s known that certain meds cause certain cancers to be exponentially more prevalent and what have you – that’s not news, because that hasn’t gotten any better. And like I said, even myself, I’m on the newest drugs now and I still can’t take painkillers because my liver and kidneys are taxed just from the HIV drugs, and years of drinking and drugs and what have you. BK: It’s still something that alters your life in a pretty profound way. DT: Yup. How I ended up volunteering at PWA was I put myself through a crystal meth recovery program called VAMP [Vancouver Addictions Matrix Program]. It was a sixteen-week program and I did that, and then I was a peer counsellor there – I facilitated group meetings for a year after that. And then part of that recovery program was I had to find something, another volunteer position to fill my time, and that’s how I ended up volunteering at PWA. Other than that, I’d never even been there, never walked in the door. I never did any support groups or anything, I just kind of just bulldozed my way through and tried to stay oblivious to it and buried it, and dealt with it as it comes. I didn’t want to be a burden to anybody, I didn’t want to suck the life out of anybody, because I always hated people that just sucked the life out of you the second they walked in the room. So, I consciously didn’t want to be that. BK: So, you really never got involved with any of those organizations earlier on? DT: No, not at all. BK: Did you have support of any other kind back in those early days, like from friends or colleagues or anything like that? DT: I always had friends, but like I said, it wasn’t something we talked about. Yeah, didn’t really – it was just take your pills, and “How are you doing?” Okay, okay. Or, so-and-so died, and you’d cry or just feel low for a couple of days and then move on, right? You tend to get a little hardened, a little, which is sad – I’m probably not as much as I should be. I still tend to well up really easy. Still losing people, still losing friends, frequently. It made me sad to see the hardware store down the street closed, because it’s almost been like a family member for the last thirty-two years. BK: Yeah, I mean the West End is sure changing rapidly right now. DT: I know, I know. I can’t believe the church is a high-rise. [Laughs] BK: It’s bizarre. DT: And I’m sorry St. Paul’s is moving too. That’s a shame. BK: That’s going to be weird. “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 10 DT: It’s going to be weird. It’s not just a hospital, there’s all these medical buildings around it, and they weren’t taken into consideration. It’s going to be weird. It’s just them being greedy for money for this land. Anyway, I’m not bitter, I swear. Any questions? BK: Yeah. So, you said you weren’t getting a lot of support from service organizations, for example, but were you getting information from them or were you accessing information from any sources back in the day? DT: There’s something else I should probably mention – ever since I found out I was positive, I’ve never had anonymous sex with anybody, I’ve never had sex with anybody without disclosing it first. I was actually picking people up online before the internet was around – there used to be a Rainbow BBS, which was a bulletin board service. There was a terminal in Numbers, there was a terminal in Denman Station, and if you had a terminal, you could dial in on your [makes modem sound] modem, and like twelve people could be online at once, and it was a DOS thing, and it was like you could see the text just writing. If you were sharing a picture, it would take like fifteen minutes, and if someone picked up the phone, you’d have to start right over. But it gave me an opportunity to write in my profile that I was positive, so I’ve always been out about being positive. I got a few people talking behind my back about it at times, I got a couple people ready to punch me in the face because of it, because I was working in a bar and what have you too – that didn’t help. Yeah, there was a lot of hostility at the beginning. People were mad at people with HIV. BK: Within the gay community? DT: Within the – yeah. A lot of whispering and talking behind people’s back. It was very much stigmatized. But there was like two or three of us that were very out front and overt online that we had HIV and didn’t hide it. I think one of them is still alive. There’s not many of us alive from back then. Like I said, it’s more good luck than good management that I’m here. BK: So, were you reading about safe sex and stuff back then too? DT: I always… Okay, I’m not good with condoms, because I precum a lot when I fuck, and I tend to just drive them in people, and it’s like – so, I generally, ever since I’ve been positive, I generally sero-sort and only go with other guys that are positive, or if I’m with somebody negative, it’s totally safe – it’s like nothing, no penetration. But all my partners have been positive. BK: That was information that you were aware of, around sero-sorting and… DT: Yeah, there was a lot of misinformation at the beginning, like there’s different strains and you can pass them back and forth, and that turned out not to be true, and a lot of just misinformation. First it was okay to take breaks from drugs and then it wasn’t and then it was. I think it kind of evolved – it’s like we learned as we went sort of thing. The information changed from one month to the next. What we were told to do was different. Another thing we were told not to do is touch cat litter, and I’ve had cats basically for like thirty years, and it’s like – I don’t go swimming in it, but I clean their litter. Basically, everything I’ve been told not to do – don’t “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 11 eat grapefruit because it makes one of the pills ineffective. Yeah, we were told not to eat grapefruit – I’ve always had grapefruit. It’s not a strict diet, but I’m not afraid to have grapefruit. Basically, I just continued my life, I didn’t really alter it that much besides taking the pills when I could and not when I couldn’t. Okay, next. [Laughs] BK: So, if there was stigma within the gay community, what were the reactions like from the exterior society outside of the community? How was society responding? DT: Well, society didn’t really know. It’s something I kept to myself. Most of my time in Vancouver, I lived in the east end or New West. The West End, I knew right away I wasn’t comfortable in the West End, right in the heart of the gay ghetto. I’m gay but gay isn’t what I am, sort of thing, so I’ve never been a marching in the parade kind of – no offence to those who do, but it’s just not me. So, I’ve lived most of my life out in East Van, in the PNE area, and I liked it there, but my HIV status wasn’t known by anybody else. Neighbours don’t need to know stuff like that. My employers didn’t know for several years – there was no need for me to tell them until I got sick, basically. The West End, the gay community can be kind of cliquey and kind of – cliquey and I don’t know, catty, definitely gossipy. But yeah, I heard people talk about me, and I heard in the bars… What do you do? It’s like, go on with your day. Yeah, it was horrible. Like I said, it was a disease for prostitutes and drug addicts and gay people, and it’s like – there was a lot of stigma that went with it. BK: I’m sure even if you weren’t telling people, like your neighbours, that you had HIV, you still would have been subjected to some stigma or heard of people saying things about HIV. DT: Oh yeah, there’s definitely two different communities, the positive and the negative. It was a big divide – not so great nowadays, the divide. A lot more negative people are tolerant of positive people, and I’m sure PrEP has a lot to do with that and the undetectable viral loads. I’ve never completely trusted that being undetectable means I’m not going to pass it to anybody, so I still to this day don’t risk anybody. I wouldn’t risk giving this to anybody. I also – personally, after losing a few people, I kind of shut down, or kind of put walls up, and I wouldn’t let anybody close to me for a while, because I didn’t want to get hurt, but more important, I didn’t want to hurt anybody else, and I knew I had this disease and I knew how much it hurts to lose somebody. So, I wouldn’t do that to somebody else, so I kind of formed a preservation mode or defence mode of having a bunch of buddies and that way no one person could devastate me, and I wasn’t going to be significant to somebody else. So, I kind of, for a lot of years, just didn’t open up to anybody. Like, I never had a one-on-one connection with – and to some degree, to this day, I still don’t. It’s just how I survived – that’s the only way I could do it. When you’re thirty-three and you lose somebody who’s twenty-eight, it’s devastating. And plus, he died of something that I had that I’m supposed to be dying from. And over and over, I buried wave after wave after wave of people. There were times I was angry that I didn’t go. BK: Is that like survivor’s guilt or…? DT: It’s hard losing people over and over and over, it’s like this constant loss, and we’re not designed for that. It’s like living through a plague, it’s like over and over, and it’s like everybody that meant anything to you is gone. Yeah, you get really apprehensive about meeting new people “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 12 or forming any sort of relationship with anybody, or any sort of intimacy or any connection whatsoever, because it’s just hurt – it’s just nothing but hurt, and you can only take so much of that. So, you do what you can to survive – self-medicate, drink, and then just put up walls. Live your life like that. Yeah, and like I said, when I could, I worked, worked my ass off, because it’s just a distraction, keep your hands busy sort of thing. Yeah. BK: Were lots of people coming into Celebrities who were also sick at the time? DT: Not so much Celebrities, more Numbers. You’d see them at Numbers, you’d see them at the Royal – or it wasn’t the Royal back then – I guess it was the Royal. The Castle had just closed, it was the Royal. Celebrities was more of a cabaret, it was more like a dance club, so if they were ill, they weren’t really going to Celebrities – it’s too high-energy, too packed. But yeah, you couldn’t walk out the door, even in the building, it’s like you’d just see people getting sick all of a sudden. You’d just look at them and think oh no. Back then, once they appeared sick, they were gone within a couple months – there was no turning back. It was usually pretty quick once they started appearing sickly – it was pretty quick. And it was really sad too because a lot of people were afraid to like touch people, or any sort of compassion or what have you. So, you’d see these couples, and you’d see one pushing the other one around who was too frail to walk anymore, in a wheelchair and what have you, and you’d just see them progressively every day getting weaker and weaker and weaker, and then you wouldn’t see either of them for a while, and then you’d just see the one. And then he’d start to get sick, and a couple of months later, he’d be gone too. It just never stopped. It was always, oh no, not him, not him, not him. It was everybody. It was indiscriminate. It didn’t matter what job you had, what status you had, yeah. It wasn’t really registering with females at that point, it was basically just a men’s disease. Yeah, and like I said, even the U.S. government was basically condoning [sic] us. You get a message like that from the government, it’s pretty hard – basically, they wanted to ship us up to a leper island or something. BK: How was the government responding here? DT: Well, there was a lot of demonstrations. I wasn’t part of them, but there was a lot of demonstrations going on about them providing medications, and ACT UP. There was a lot of activism going on. Yeah, it took a lot of people making a lot of noise before the government stepped up. They were unwilling at first to give us any support. They basically just wanted to sweep us under the rug. Even to this day, our HIV meds are paid for, but there’s a lot of other meds that are quite often needed that aren’t covered. It’s funny, if you’re in the hospital, they’re all paid for, but if you’re not in the hospital, they’re not paid for. It’s still – we could still go a little further. There’s some other supplemental drugs that could go with the HIV drugs that could be covered, I think. BK: Especially when a lot of folks are living on disability. It’s like, even a relatively… DT: Well, generally if you’re eligible for provincial assistance, then most of this stuff is covered, but because I make CPP disability and then my private insurance, I make too much – theoretically, too much money to get any assistance from the province, so I get nothing. So, I’m kind of stuck between a rock and a hard place there, because I don’t really make too much “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 13 money. Yeah. My rent is basically 75% of my income, and then throw bills on top of that, and it’s like – and it’s getting worse every year. Like, I don’t have cable, I share my internet with my neighbour, do what I can. Yeah, and I don’t want to leave Vancouver because basically the care is here, so if I move out to where rent is cheaper, then I’m not going to be close to care again, and I’m kind of at a point now where I need to be close to care. Yeah, we’ve lost a lot of people. I always take Remembrance Day and I always think of the people I’ve lost, because I kind of consider that a war. BK: Do you think we’ve done a good job as a community of remembering this period and the folks who have passed on? DT: Not particularly. I think a lot of it’s just trying to be swept under the rug, and it’s like – it’s being promoted now that it’s no big deal and it’s being treated like it’s no big deal. It’s like it’s something treatable, like all you need to do is take an Aspirin a day and you’ll be fine, and it’s not the case at all. And I think the people nowadays don’t realize what they’re doing with their lives. I think – well, when you’re twenty, you think you’re going to live forever, right? You don’t think how it’s going to affect you, you don’t think that you’re going to go on and on and on, and you’re going to go downhill, and you’ve got a lot of years to go yet – you don’t think like that when you’re twenty, twenty-five. So, I don’t think they’re really getting that message. I think there’s still a community out there that’s looking to be infected just because they think there’s more benefits in it. They can get supplements, they can get housing, they can get retreats, they can get all these food supplements repeatedly, and all this stuff. I think there’s still a community there that thinks they can benefit from becoming positive. There’s still people who are potentially becoming positive. Actually, I know there is, because I know quite often, I’ll hook up with somebody, and they’ll be like, “I’m negative but you can fuck me.” It’s like, no, I can’t. They just don’t care, they just don’t seem to think it’s important anymore. So no, I don’t think that they really know what is was like, have any idea what it was like, know how many people died or anything. I know there’s the AIDS memorial wall down there, but a lot more people than that died. Yeah, I don’t think they really – I don’t think it’s really known how bad it was. If you weren’t there, it’s hard to describe. Like, just watching Dr. Peter lose his sight every week on CBC and just watch him decline and what have you. Yeah, it was hard, especially when you’ve got it too and you’re thinking it’s going to happen to you right away because you’re told it’s going to happen to you right away. BK: It’s like looking into the future. DT: Yeah. I don’t know. I don’t know why I’m here. [Laughs] BK: How can we do a better job of remembering this and preserving the memory of some of these people who have passed away? DT: Maybe do like a historical biography type thing and put it on YouTube. Maybe re-run the Dr. Peter tapes, because that really showed the whole community back then, right? I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t know if there is an answer to that. I think – I’ll say it, [undecipherable], I think a little less self-promotion saying we’re the only hospital who’s closed a ward for HIV, and stuff like that, and basically denouncing [sic] that we’re on the decline. “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 14 They’re sending a lot of messages along those lines, but that’s not a message that should be sent out, I don’t think. I think that message is wrong. BK: We’re getting the message that AIDS is over, right? DT: Yeah, exactly. It’s chronic, it’s not important anymore, it’s something you live with, it’s nothing urgent anymore. If you get it – basically, most of them couldn’t even tell you what AIDS is anymore, it’s all HIV now. Is it still AIDS? Do they still have AIDS? BK: I don’t think people talk about AIDS at all. DT: I don’t think so. It’s a different time. At least now people aren’t afraid to hug you and kiss you and what have you, so there is education along those lines, so the general population is not terrified of us anymore, they’re not hostile toward us. I haven’t faced any hostility in ages. Yeah, we’ve come in the right direction in that area, but I think we’ve understated how important – realize what a serious disease it still is. I don’t know how to deal with that. I don’t know. It’s not like you can make everyone take a course. And there are people who just don’t want to know – they’re happier, ignorance is bliss sort of thing. But you know, being on the retreat team for PWA and facilitating small group meetings, I got to listen to other people’s stories. I’ll tell you, as bad as mine is, there’s a lot of people who have it a lot worse. I heard horrific stories. I survived mine and I’m still here and relatively sane. I have my good days and bad days, and can’t always remember why I walked into the kitchen, but… [laughs] BK: Yeah, we’ve heard a fairly broad range of stories at this point, and there’s a lot of horrible ones. DT: I heard – this should be about me – but I had in my small group this Mexican kid who, his boyfriend – he just moved here, he barely spoke English. He slept with some little hustler here and this little hustler threatened that if he wasn’t going to stay with him, he’d go to the police and tell them that he infected him, and he did, and he ended up in prison. YouthCO got him out of prison. Yeah, his family disowned him in Mexico. He was just like eighteen, nineteen years old, no English, didn’t know anybody here, and got thrown in jail. A woman from the Congo who got raped by someone in the military and had to leave her four kids there and never see them again, and sneak out of the country or she would have been killed, and never turned back. She actually started a not for profit group for HIV positive African women here in Vancouver. I met some incredible people. Yeah, it’s amazing how resilient people can be. BK: It is. It really is. DT: Must keep swimming, must keep swimming. [Laughs] BK: I think we’ve covered most of my questions. Another large question: how did HIV change the gay community here in Vancouver, thinking as a whole. DT: I think it made it more pensive, not quite as – not your free love or anything like that in the ‘60s – people don’t just jump into bed. Well, I shouldn’t say that – the bathhouses still exist and “HIV in My Day,” Don Tenden (May 6, 2019) 15 anonymous sex, those places still exist. I think Vancouver is probably the same as every other city in the world. I think it’s destroyed a lot of lives, took a lot of lives, and the ones that are left behind are shattered and damaged. Yeah, people are pretty fucked up over this – like, it’s hurt a lot people very deeply, there’s a lot of scarring. And there’s always differences of opinions and what have you that can be a dividing line for friendships and what have you, because people see things differently and have different views. Like, I don’t use condoms, but I consider myself having safe sex only having sex with other positive people – I consider that safe. Other people don’t, and some people feel very strongly about that, right? So, things like that can really cause tension in the community. Yeah, I think it helps divide the community a bit, not like it used to. Like I said, it was very black and white – positive and negative. It’s come a long way and education has come a long way, but there’s still a dividing factor for a lot of people. There’s still people who refer to themselves as clean – like, “I’m clean.” BK: I hope that’s becoming less common. DT: I don’t think it is. It would be nice if it was because it’s just like what are you implying? Don’t you hear what you’re saying? I know it’s not intentional, it’s just the way it is. Sometimes people’s terminology is just – it will be one of those things that’s not politically correct in ten years. BK: I suspect so, yeah. We talked a bit about the younger folks out there in the community who didn’t experience this period of the epidemic, but do you have any advice for those young folks out there who didn’t live through this? DT: Don’t throw away your whole future for a romp, you know? It’s just not worth it. You’ve got a lot of years to live, you’re going to live a long time yet. You’re not going to be twenty forever, you’re not going to be twenty-five forever, you’re going to be fifty, you’re going to be fifty-five, sixty. And when you’re positive, your body breaks down – the pills are toxic still, the virus is toxic, or it’s a virus. Don’t throw away your life for a fuck. Yeah, that’s it. Smarten up, give your head a shake, think about what you’re doing. Sober up. Think about it for a day before you do it. And really, there isn’t enough benefits to make it worth becoming positive, trust me – the negatives far outweigh the positives. Don’t throw your life away. I wouldn’t wish this on anybody – it’s hard. It’s hard losing people, it’s hard being sick, it’s hard being sickly. Like, two years ago, I was walking around with a walker. I’m fifty, fifty-one years old, and that wasn’t supposed to happen. I was supposed to be working, vibrant, not cared for, living on insurance and Canada pension. That’s not how it’s supposed to go. Yeah, use your head. It’s a lot more serious than they’re letting on. BK: I think we’ve covered all the questions that I would have asked, but we always like to leave some time at the end of the interview just to ask if there’s anything that you wanted to expand upon or add before we turn off the recording. DT: No, I think that’s pretty much it. My life’s an open book. You’ve only got one life. Take care of it. And try to live the best life you can. Okay. I passed. BK: Thank you so much. I’ll just stop this.

An interview with Don Tendon as part of the HIV in My Day Oral History project. Interviewer: Ben Klassen. Location: Vancouver (Momentum).

- In Collection:

- 00:22:26 (Part 01)

- 00:46:39 (Part 02)

- 49.24966, -123.11934

- HIV in My Day

- Lachowsky, Nathan

- Vancover Island Persons Living with HIV/AIDS Society

- YouthCO HIV & Hep C Society

- Rights

- This item made available for research and private study. For all other uses please contact Dr. Nathan Lachowsky.

- DOI

| Thumbnail | Title | Date Uploaded | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Interview with Don Tendon Part 01 | 2021-05-31 | |

|

Interview with Don Tendon Part 02 | 2021-05-31 | |

|

|

Interview with Don Tendon transcript | 2021-05-31 |