Interview with Erik Ages

Add to collection

You do not have access to any existing collections. You may create a new collection.

Downloadable Content

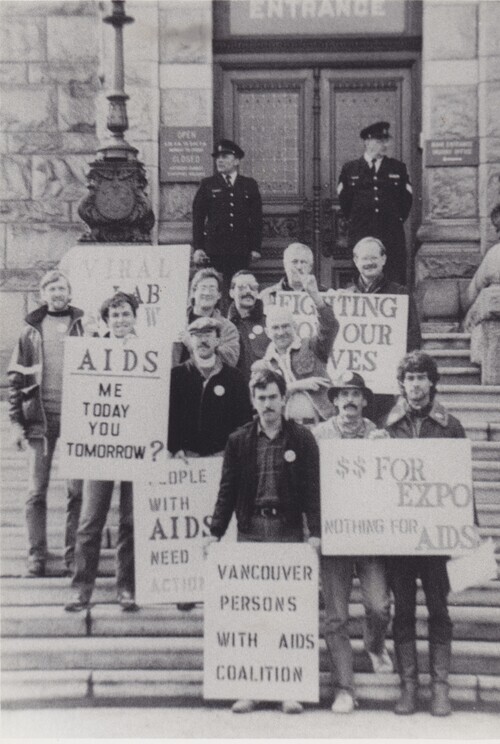

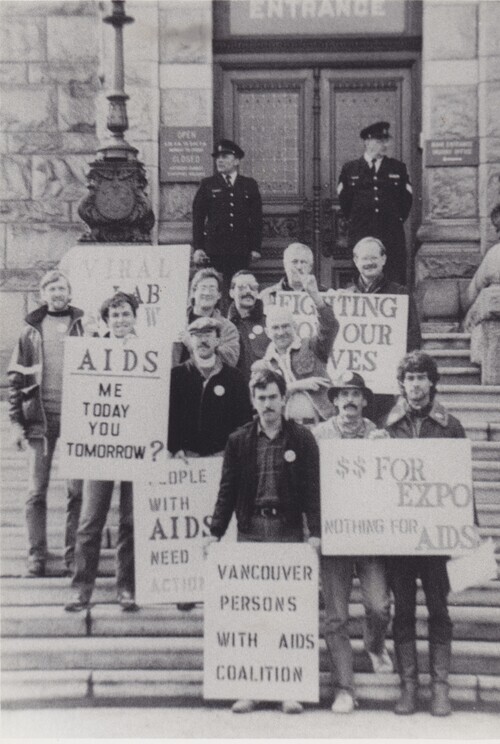

19-04-17-EA.docx “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) “HIV in My Day” – Interview 80 April 17, 2019 Interviewee: Erik Ages (EA); Interviewer: Ben Klassen (BK) Ben Klassen: Great, just getting started talking to Erik. It’s a beautiful day in Victoria. Just to get started, when did you first get involved in the gay community or start engaging in gay life? Erik Ages: Oh, I came out to my mother in the dining room of the Empress Hotel in Victoria, with my mother and her lover – my mother was a lesbian at the time – when I was thirteen. So, my mom and her lover took me for my birthday dinner at the Empress and we had Chateaubriand, it was full French service and everything, it was a big important thing. And I came out to my mom and [mom’s partner’s name] over dinner. BK: Wow. That’s quite incredible. EA: I was a little precocious, but I had a kind of family background that permitted a wide range of behaviour, and my parents were academics and intellectuals, and kind of bohemian, I guess. BK: So, after that point, when did you start connecting with the community, so to speak? EA: Oh yes, right. Probably when I was fifteen or sixteen. I started – I briefly dated a much older man who was twenty-nine. My mother was very upset. He had a motorcycle. I think she was more upset about the fact that he had a motorcycle, but I think she was just upset. Anyway, this fellow was the friend of a woman whose child I babysat – that’s how young I was. So, that was my first sort of encounter, sexual encounter, and then I began going to a local Victoria gay bar when I was about fifteen or sixteen – I was underage. My biggest fear was meeting my mother at the bar because I was underage, because the chances are she might have shown up there, but she never did. BK: What did the gay community in Victoria look like back then? EA: Yeah, back then – back then would have been – hold on a second… the late ‘70s, I guess. It was a strange existence to be – my family home was sort of the vortex of the women’s movement. My mother and all of her colleagues were very, very active in founding and creating infrastructure and institutions for women – BC Federation of Women, the Victoria Sexual Assault Centre, the University of Victoria Women’s Studies programs – all of that. So, our house was full of those types of discussions, and we had visitors from all over North America at that point. It was very exciting as a kid. The contrast was to go to gay bars, and gay men were generally drunk and unsophisticated in terms of their definition of community, and my sense even back then, I was able to be highly aware that it was based on shame – it was shame-based. And so, it was an unusual circumstance to have the resources and the language and passion of the women’s community that I was exposed to on a daily basis, punctuated by brief forays into what would have been the men’s community, or a lack thereof, that really revolved around alcohol. BK: And sex. “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) EA: Yeah, yeah. BK: So, it wasn’t necessarily, in your view, the most politically sophisticated community at the time? EA: Oh, it was profoundly depressing. It was really depressing. It was demoralizing. It’s funny that a lot of the men were living with internalized shame. I was dealing with a kind of shame on their behalf, so I wasn’t personally ashamed, or at least it wasn’t something that I was operating with, but I was certainly embarrassed by – I was embarrassed by the quality of life that was being demonstrated by gay men in bars, which back then was the only way that men could meet each other, and I appreciate that. BK: Was there, like, one gay bar in Victoria at the time? EA: There was, yeah, one way back then – it was called… what was it called now? I can’t even remember. The Carleton, I think. Anyway, whatever – it doesn’t matter. At least it was upstairs and not in a basement, because back then, Vancouver was the same. The Vancouver bars, which I also experienced around the same time, were all generally basements or dark things reeking of alcohol. I played my part, I drank my way through my twenties – teens and twenties. BK: In comparison, was the gay community in Vancouver a lot bigger? EA: Oh, of course. So, the gay community in Victoria was, I think, as far as I knew, there was a sort of mysterious park sex going on, which back then, it was far too frightening for me to even think about it. And then there were – I guess there were newspaper ads of some kind that I think that people used before – back then, there were calculators, that’s it. And then I think there were phones – I never tried any of that – and there were bars, or in the case of Victoria at the time, there was only one bar. BK: So, when did you first hear about HIV or AIDS or GRID? EA: I was twenty-three – twenty-three, I think. I had finished a stint of art school, writing, and then I was in either Camosun College, which is the equivalent of Cap College or something, and then UVIC, and I think I was actually in UVIC at the time – I was an undergraduate. Being gay at that point had almost nothing to do with me, and I was dating a girl, actually, at that point, who was madly in love with me. And I wasn’t actually aware of anything until a friend of mine indicated that – I was kind of like straddling both worlds. I was like an aspiring young academic, scholarship track, you know, just completely addicted to school, and then I was making occasional forays into gay bars at the time. We’re going to be interrupted… [Recording paused] BK: So, I was just asking when you first heard about HIV or AIDS. EA: So, I think I was early in my undergraduate career, and I heard of someone who was sick – that’s what I heard. Nobody knew what these things were yet, but someone was sick. And then there was this kind of weird inarticulate kind of brushfire of rumour that people were getting sick “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) for no other reason than they were gay. I only knew of one at the time, but then about six months later – not very much later – a man that I had been briefly lovers with when I was eighteen, young – he was probably in his forties – he got sick too and he was in the paper. And that’s when I became afraid, because he would have become ill when we were together, so he was – I remember he was making frequent trips to San Francisco, and he was definitely a bathhouse kind of guy, and definitely very active. So, I became kind of anxious and worried about it, and then I sublimated that, I just sort of moved on with my exams and papers – I was an undergraduate English student. Then I had hemorrhage in my retina, my right retina because I can still see it every day, and I went to a retinal specialist, and he was a kind of pasty, anxious-looking fellow who looked like he’d always failed to thrive, and he found a profession where he could be kind of mouse-like. Anyway, he put his hand on mine – it was just before Christmas, it was before my mid-term exams – and he said, “Are you gay?” And the fact that he asked me that in the context of – without any other questions to frame that question – I’m not a stupid person, so I made an immediate connection, and my heart started racing, I became afraid – I was terrified. I left that specialist’s office in a blur. I remember not knowing what to do. Like, I couldn’t see out of my right eye – it had gotten worse and worse. I went back to my mother’s house – I rented the suite on the top of her house – I walked into her floor and told her that this specialist thought I had AIDS, which is the conclusion that I drew. And back then, there was no middle step – that was it. And I spent weeks in my bedroom holed up with the door closed listening to CBC radio, and CBC was full of interviews of young men dying. It was just awful, it was awful. I was terrified for weeks until I got the results of my HIV test, which they actually had, it just took a long time. So, I went to my physician, my GP, who had been my GP since I was fourteen, and he’s the GP that was staffing the STD clinic, which was a shock to me. So, I’d go in to get an anonymous test and there’s my GP to administer the test. [Laughs] But that was okay. In the grand scheme of things, everything was okay, because the only thing I could focus on was the fact that I was dying. Anyway, my eye, no thanks to that specialist, eventually cleared up. My girlfriend at the time was leaving plates of food at my door, because I wouldn’t answer. It was like I became closeted just prior to that, and it was partly out of embarrassment for the gay community, which I alluded to earlier, that it was this non- functioning kind of drunken brawl of desire and incompetence, and my own residual fear about these little points of fire in terms of people dying in unexplained and very rapid ways, so I was deeply conflicted. But I was conflicted in a way that wasn’t unconscious – I was very conscious and could articulate the conflicts that I was going through at the time. That didn’t change or help anything. The physical affect of experiencing that fear and loathing, you can be as articulate as you want to be, but the physical moving through that process doesn’t change, it’s still fear and the gut-wrenching need to be isolated. That’s my answer to the question. BK: So, then you eventually got your test results back. EA: Yeah, which were negative. Even then, I didn’t quite believe the test, and I attributed what would have been a positive result to the fellow who died who had made frequent trips to San Francisco at the time. But yeah, I was negative, and I continued through school and somehow managed to pull off straight A’s and a fellowship, things to go onto graduate school in London, Ontario. “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) BK: So, this would have been ’84-ish? EA: Yeah, I think so. Yeah, that’s about right. BK: I’m just guessing from what you’re saying about the test. As the ‘80s progressed, was there a lot of useful information out there for you around HIV and prevention, or not so much? EA: I think I got most of my information – I was disconnected from the gay community during that period. When I went to London – as I mentioned earlier, I’d grown up in a somewhat socially progressive circumstance. Moving to London was a culture shock, because it was a much more conservative environment, and there was a gay bar there, but you had to sign in like back in the ‘40s and ‘50s – it was members only. And nothing compared to the sort of permeability that existed in clubs in Vancouver and Victoria, so it was definitely – like, literally closeted, literally, because there were gatekeepers, and their role was to prevent people going into those enclaves of alcohol and desire that should not have been there. Anyways, so it was a bit of a throwback for me. Again, I remained disconnected from that whole world. I was, I think, celibate for years – ever since that misdiagnosis, I was a kind of academic recluse, and absolutely celibate with a few drunken mistakes along the way, which were so drunk that they were basically blackout periods. Anyway, even then, during this period, that didn’t happen, it happened when I moved to Vancouver that I kind of let loose on occasional weekends. But most of my information about HIV I gleaned through CBC Radio, through books – Randy Shilts, Armistead Maupin, all of this sort of world stage writers. And people on the world stage were bearing witness to this, but locally, no. Locally, I regarded local gay communities with the same contempt that I had regarded them since I first came out at a very young age. BK: You talked about not having much of a sex life for a couple of years. Was that a conscious decision? Was that made in light of the risks that were out there, or more of an affective thing where it was your body shutting down due to the fear? EA: It was both. And I don’t even need the benefit of hindsight to be able to attribute the sort of quashed desire out of fear, out of varying goalposts about what was safe and wasn’t back then, because the goalposts kept changing, and from what I could tell, the only safe stance was abstinence, certainly early on. And remember, I mean, there was a lot of – there was fear within the gay community during that period, but profound fear in the general society, so it was really hard to take a middle road during that period. Anyway, and the other thing was I just didn’t feel any desire. BK: Do you remember what was being said in some of those mainstream perspectives on the epidemic in those early years. EA: Certainly. Shame and fear – fear was most of it. In terms of mainstream responses, I can never forget the short pieces on CBC Radio where young men were being ostracized not just by their families, but by whole communities insisting that they move out, young children who were diagnosed for whatever reason being asked to leave their schools. I mean, there was – with the exception of people in public office and sophisticated bureaucrats, policymakers, the general public was reacting with the need to ostracize. Generally speaking, that was their response, “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) which is very tribal – it’s a very instinctive, tribal kind of response, and I was aware at the time that the goal of people in creating policy was to buffer those base instincts in order to protect the greater good and the individuals who were vulnerable within the greater good, if that makes sense. BK: So, I guess that would have manifested as a spike in homophobia at the time – did that coincide with this in any way, shape, or form? EA: I’m not so sure – around that time, maybe a little later – I don’t know when Angels in America came out, but the guy who started ACT UP, that brilliant fellow from New York… BK: Larry Kramer? EA: Ah, Larry Kramer, yeah. He wrote a book called Faggots that came out I think in the mid ‘80s – I think it was around there, I don’t know what the date is. Larry Kramer – again, I was an academic, I was reading for information more than I was getting it from the public or from the gay community, certainly, so Kramer’s book was very critical and harsh about the gay community. It was a very critical look at the gay community, and I remember thinking, applauding Kramer for having the courage to take a stance against the political correctness of the most liberal ends of the gay community who were fighting back against institutional steps to protect people. The gay community – some at the time – were saying this is absurd, this is a conspiracy, blah, blah, blah – really it was there – “they’re just trying to stop us from having sex.” I mean, really, it’s in the literature, it’s there, and that kind of ignorance was what Kramer was pushing back against, and I was a big fan of Mr. Kramer. BK: Was HIV showing up in your personal life at all during this period? EA: I didn’t notice it. Again, I was detached, I was just studying. Once I moved from London, Ontario, I moved to this Killam Fellowship at UBC to do my PhD in English. I arrived there, and it’s then that I kind of – I felt safe, finally. I felt safe for a whole number of reasons – I had a good friend, a fellow academic, who was living with me, a woman. We were friends, still are. We lived in a spectacular waterfront Kits penthouse looking over Kits pool. My mother furnished it over the summer while we were travelling, and we arrived and the whole thing was furnished, with Persian carpets and silver and everything – it was like moving into Architectural Digest. A chain of events – the fellowship, this beautiful home that was affordable and vast and spectacular, my schooling, which was rewarding – I felt safe. And out of that safety, for the first time, I began to – I became, like, ultra-fit, so I was biking out to UBC, I had a part-time job in Metrotown, so I was biking from – I was hyper healthy, and that made me feel safe too, that sense of vigor and health. I think that unconsciously was my pushing back against this environment of illness because I knew it was there, I was surrounded by it, even though I had no one I could identify with who was still alive who was living with HIV, I knew it was all around me. I was pushing back in ways that I could, and then I started to loosen up in Vancouver, and I started dating, and I was young and attractive and fit and all those things, and was very successful at that project of dating, and had a lot of fun. For the first time ever, instead of it being fearful – and it was fearful even as a kid before HIV it was fearful because these older men, I “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) didn’t know them, and their world of alcohol and dark bars was like, what the fuck is this? Why are people living like this? It was always alien to me. Anyway, at UBC in Vancouver, I started to branch out, and then in the midst of all of that, old friends of mine who I had gone to art school with who were either fellow students or – I became aware that they were ill. Out of that sense of vigor and health that I had, I felt a commitment finally to give back, that I needed to do something. And so, I volunteered – I had time to volunteer as a graduate student – I volunteered at AIDS Vancouver with the helpline first and the speaker’s bureau next, going to schools and so on. I thrived in that environment, I found it very rewarding, and during that same period, which would have been later ‘80s, old friends and dear friends of mine, they started getting sick, because people’s progression through HIV, the early onset ones were the ones that started the fires first. People were aware of those deaths early on in the trajectory of the disease. Those who progressed more slowly, like ten years or whatever it might be, those are those the ones that started getting sick in the late ‘80s. Without any medication, they were fine until a certain point – you must know all of those details in the background. But a lot of those people were my friends, so my exposure to friends and acquaintances who I loved with HIV came hand-in-hand with my parallel involvement with AIDS Vancouver. They weren’t linked, they kind of happened in step with one another, if that makes sense. BK: So, you found yourself involved with this ASO, but you were also involved informally in supporting your friends, just being there for your friends? EA: Yeah, yeah. What’s interesting is that one dear friend who I looked after on a regular basis right until he gave up and died, he was an old art school friend of mine when we were in art school in Nelson together – lovely, beautiful man, and he was my age. He had no relationship to the AIDS community at all, so it’s a kind of flip of the coin to when I was a kid with the women’s movement, and gay men, aside from being drunk, had nothing to do with building anything. And then we had this AIDS movement, and then I had these gay men who I’d known for many years who I didn’t really actually know as gay – I didn’t know they were gay until much later. I’ve never had good gaydar ever, ever – like, zero. My staff at work tease me about it constantly because I have fifty-five employees and they all know I’m gay, and we have some gay employees too, but I have the worst gaydar in the entire fleet. Women I can spot immediately – lesbians, it’s like I got them, but gay men, not a chance. Anyway, these guys weren’t affiliated with the AIDS movement at all – they had no interest in it. They were hospitalized and sent home, and hospitalized, and prophylaxis for whatever they needed at the time, whatever the technology was at the time. Their interface was through the hospital and not through the gay community at all, so it was kind of like a split existence at the same time, because I was becoming politicized. For the first time, gay men were actually building and organizing things – for the first time in my experience. And it always irritated me, pissed me off, that it took a kind of mass suicide to motivate gay men, whereas on women’s side of things, it just took a sense of social justice, and it still pisses me of to this very day that men needed a bigger push to jump off that cliff of inertia and indifference than it took women. Women, in my experience – well, I guess you could look tribally at the fact that they want to build relationships and community, but I expect better of men in general. “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) BK: Were women jumping on board with the AIDS movement too? EA: Absolutely, absolutely. There were two different kinds of women that I remember at AIDS Vancouver. There were the political zealots and deeply motivated, intelligent people – some were too passionate, some were clever. Then there were what I call the BMW ladies, who would arrive at PARC [Pacific AIDS Resource Centre] – I don’t know if you remember PARC but AV, PWA, Positive Women’s Network all joined together – I was involved with it at the time when we were on Helmcken, and actually before Helmcken. So, we moved to Helmcken as the shared resource, and all kinds of BMW ladies, which were affluent women who could have been contributing or volunteering for the art gallery – it made no difference to them. And they would be walking up in their Chanel suits – I exaggerate – up to the upstairs of PARC, and these itchy, skittish, emaciated men would be running up and down the stairs saying, “Oh my god, I’ve got anal herpes” – all this kind of stuff. It was a deep contrast. But there was the kind of stalwart left- wing women that were the kind of women that I grew up with, who were involved with the AIDS movement in lockstep with the few male leaders in the field at the time. And then there were the social do-gooders who drove luxury cars and lived in North Van. BK: We haven’t heard as much about those people. We’ve heard a lot about lesbians stepping up, and people who had feminist backgrounds, for instance. EA: Oh yeah, sure. BK: But BMW ladies, they’re new to me. EA: Oh, they were there, absolutely. I recognize them because I grew up with BMW ladies, so my mother’s family was full of BMW ladies. My mother drove a Volkswagen station wagon, and she was definitely the oddball, but that milieu of women were definitely involved in the AIDS movement, no question about it. BK: So, what was AIDS Vancouver doing at the time while you were volunteering there? EA: Well, back then, it was really dealing with fear – on the part of the public, it was dealing with fear. So, fear on the one hand, and then care and advocacy on the part of patients to get drugs that were still in pipelines, to find, to challenge doctors and institutions for prophylaxis, which back then was really the only preventive treatment that there was. So, they were doing that. They were doing the sort of academic, institutional approach to advocate on behalf of people who were sick, and then on the public end it was dealing with fear and trying to educate and be clear about prevention strategies to people who were afraid. The teaching methods and the amount of information you can get across to people who are terrified is a challenge, and that’s what AV and other ASOs around North America, that was their biggest challenge was to figure out how to communicate the principles of prevention to people who are so afraid, they aren’t listening. So, that’s what it was like in the early days. BK: And that message was kind of coalescing around this idea of safe sex at the time? EA: Yeah, oh yeah. It was – safer sex, yes. “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) BK: You said simultaneously you were getting involved on a more personal level with your friends. What was it about ASOs that maybe your friends didn’t connect with – I’m just curious about whether you have any ideas about that? EA: I thought about that at the time. These were men who were self-sufficient, they weren’t political, they weren’t interested in politics, and one of the – what was inevitable in the development of ASOs back then was it was fight to the death. Like, it was – the stakes were very high and people of all stripes and all backgrounds were afraid, including the people who were building ASOs – everyone was afraid or angry. And the ones that – the evolution of ASOs came out of anger and a profound sense of social justice, and the need to just rescue people. And so, it was highly political by virtue of the environment in which they sprung up because nobody could be indifferent. It was not a medical clinic or a travel agency, it was highly political. The very fact that it existed was political. And so, there were lots of gay men in my experience – lots meaning the few that I knew and their friends, and so on – who had no interest in being political, they just wanted to live. And as the disease progressed, they wanted to live on their own terms, and they didn’t want to be political objects. BK: What was it like being in a caregiving role to some of those people? EA: Sort of hopeless – in the early days it was hopeless because, you know, immunosuppression, even now is a big challenge, but back then… I mean, we have AIDS to thank for all kinds of advancements in terms of dealing with people who are immunosuppressed. A lot of my friends and friends of friends all over the world died, and the learning curve that the medical profession underwent in all sincerity, but it improved because of this great big petri dish, this great big population of trial runs around how to deal with immunosuppression. So, it was kind of hopeless – there was really nothing to do. I think there was AZT and DDI and a few things early on that – people were taking them, there were side effects and all kinds of things. Some people couldn’t take them at all, and even if you could take them, it’s like, well, is it doing anything? Nobody knew. People were trying anything. [Name], my dearest friend, and he’s the one that I cared for daily, and I remember he was in the hospital most of the time over the last – he was in the hospital a lot, at St. Paul’s, which was where I was born, so I remember the poetic sense that I kept visiting this hospital all the time, I was born there. He knew he was dying, and eventually he stopped the fight – like, he got sick – he and other people got sick of all the medication, kind of like cancer therapies – eventually, some cancer patients just say, I’ve had enough, this is enough. And [name] reached that stage, and I remember being shocked that he was twenty-eight and aging before my eyes, not physically, although he was emaciated at that point, but he was aging psychologically – he had become someone in his eighties from the perspective of his soul. He was worn out, and to be worn out at twenty-eight, I remember observing that, and that really struck home, that that kind of evolution can speed up and you can basically go through your life within the space of a few years and reach the sense of closure within twelve to twenty-four months. Because he wasn’t caught off guard – he knew, he was prepared. And parallel to this, I was, you know, being political at AIDS Vancouver, and then I would go to St. Paul’s and politics had nothing to do with it, it was just intimate daily care, with a sense of resignation and hopelessness. “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) BK: But that sounds political in its own way, valuing your friend’s life. EA: Yeah, totally. BK: You’re talking about how this was kind of a petri dish for the leaps and bounds that the medical system took during this time in terms of how they treat immunodeficiency. EA: Well, it’s astonishing. It’s astonishing how quickly medical professionals and researchers around the world mobilized – who cares why. I think it’s well-intended on most parts, but certainly pharmaceuticals and all kinds of enterprises and institutions mobilized to get this done, and they were cooperative in many instances, and that too was unprecedented. Rather than cloistering themselves as institutions, they were working together in order to speed up the learning curve. I was aware of that back then and I was impressed by it back then, and I don’t know how it happened or if it’s happened since – I don’t know, I’m out of touch now. BK: Were you aware of some of the AIDS activism that was going on in Vancouver at the time? EA: Yes, oh yeah, and I was involved. I was hired on at AIDS Vancouver, I became a full-time staff person. I quit grad school and started working full-time at AV and PARC by extension. I was one of the founding board directors of PARC when I was thirty or something, I remember signing the document, the charter document or whatever it was. Not through intent, it’s just I happened to be in the room. I’m proud of that. I’m proud of the day-to-day work that went on in places like that because without it, and without the persistence of ASOs, as clumsy as they were, because they were community-based organizations, so the skillsets that are brought to bear on those places are hit and miss, right? They’re not professional, but that to some extent is their advantage, because they don’t know how to be polite, and so they were abrasive and abrupt and loud and noisy, and I think they actually did achieve – they achieved good things as a result. So, I was definitely involved. I was the assistant to the director of education, full-time on salary through Rick Marchand, and then when he moved into the position of executive director, I followed him, and I became the assistant to the executive director. And then I was hired over to Victoria, AIDS Vancouver Island, and I became the communications and fund development coordinator, and brought the AIDS Walk to Victoria which was highly political back then too. And it was a very public position, so I was in the media a lot, and I was pretty polished and professional about it, so I was useful to the media because they could count on good soundbites – not as long as these ones. I remember Princess Diana died right around – whenever it was, I don’t know – I have no memory of when it was anymore. She was a big deal, she was touching people with HIV, and that was back during periods of fear when the idea was verboten. And I remember giving good soundbites about Princess Diana, and I remember thinking how do I talk about this woman who I don’t know with some taste and sensitivity to the fact that, you know, the media are hungry for content, and I needed to say something that was useful to AVI, useful to the AIDS community, and respectful to this woman who had just died. And I think I came up with something in advance, because I was prepared for it – I thought, god, I’m going to have to comment. I was prepared and I said something to the effect that Princess Diana demonstrated leadership during a time when statesmen around the “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) world were not, which I thought was – I felt okay about doing that, because it was sensational, right, which made me uncomfortable. I don’t want to fuel other people’s fires. Anyway, so in my role over at AIDS Vancouver Island, it was very public, and Victoria was a little bit behind Vancouver in terms of social acceptance of AIDS, which by direct link meant gay men, which made people uncomfortable, and I was a public figure during that time. BK: And by extension, you kind of were out as well, right? EA: Absolutely. In Vancouver, I met my real only lover when I was thirty – I had just turned thirty. And he and I, we went to the Pacific Centre mall to a jeweller’s – this was back in ’91 – to buy wedding rings, and the jeweller in the Pacific Centre mall was horrified – this woman, she blanched with disgust, I remember. I felt no – because of my upbringing, my willingness to apologize for who I was was zero – like zero. So, I wasn’t shy or withholding about who I was – internally I was sometimes, but externally, not a chance. So, we got these rings despite the objections of the retailer and exchanged rings in the law courts on Howe St. – there’s a little Japanese garden sort of in one corner – and a security guard came up and thought we were doing a drug deal or something. [Laughs] But we were together for nineteen years, and really, ultimately it was the only relationship I ever had except for forays into the mess of anonymous gay life. We moved to Victoria together and we were a very out couple, and we were an out couple in Vancouver as well. BK: How long were you at AVI for? EA: Probably five years – four years. So, right up until maybe 2000 – something like that, 2001. BK: And why was the AIDS Walk considered so political at that time? Just because of that connection with gayness? EA: Oh yeah, back when it was first introduced, yeah. But it was very public, but what really was exciting about that project was the big sort of media celebrities in Victoria, for what they were, latched onto this project, and we did incredible work. We had TV spots and fairly sophisticated promotional ads that were in print, TV, radio – like, we really were slick. And the AIDS Walk in Victoria was really successful, it was really awesome, and it mobilized people. And it was around that period, the whole AIDS Walk concept in Vancouver and then in Victoria was a chance for people to feel like they were doing something positive rather than just living in despair and with a sense of resignation that it was hopeless. The AIDS Walk in its first years was a chance for people to say, oh my god, there is hope, just by virtue of us being here together. And that was a cultural shift that is important to recognize because before then that would have never been possible. And I don’t know what triggered it, that sense of – I mean, back then, if you went to the Castro, you would have seen the same thing, this kind of despair in San Francisco, this ghost town kind of quality that wasn’t just in San Francisco, it was pervasive, which further exacerbated that kind of vestigial shame that was of that generation, that sure they were all liberated and all this kind of stuff, but it was grounded in shame. I don’t know if it is anymore, I hope it isn’t, but back then it was. And the AIDS Walk was a kind of rite of passage, and kind of like a wedding ceremony where everyone celebrated the achievement of community, which is “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) what a wedding is. Anyway, that was a kind of moral victory, the fact that those events were successful for as many years as they were. BK: My impression is that another impact is that it was one of these moments where mainstream society got on-board in a really public and obvious way. EA: Yeah, absolutely. BK: So, it wasn’t just gay men who were a part of that. EA: Totally. Yeah. BK: I was going to ask about PARC too. How long was PARC a thing for, because it didn’t stay that way for all that long? EA: I left before PARC evolved past its PARC-ness, so I think that BCPWA, AV, and PWN were trying to share resources and reduce costs, and it made good sense. And the fact that the whole idea back then, I was involved in creating its first annual report, and I remember we hired this slick communications company to do some of the work, but I was tasked with the writing and working with photographers – project managing it. And the messaging behind all of it was “one-stop shopping,” because people affected – I mean, there’s mobility issues, there’s poverty, there’s all kinds of things that people who were living with HIV were facing, and so if we had one location that had a food bank, that didn’t just serve gay men but served women and people who were street-involved – whatever it was. Street involvement was a tiny sliver of the work back then – drug use, that type of thing. So, the whole idea was a good one, it was a good idea, but politics, in particular the identity politics took over, and identity politics between people who are drug-involved, gay men, the BMW women who weren’t interested in the drug-involved people, they wanted to rescue gay men. The affluent people wanted to rescue the bright lights – the bright lights were the fashion designers, the hairdressers, the people who amused and entertained the people who wanted to do the rescuing. Once the influx of drug use from the Downtown Eastside and so on started presenting with HIV and then HCV – which was kind of a separate learning curve. And then all of the associated problems, like herpes, and all of these things that nobody – it was like woah, what is going on? We don’t know how to deal with this stuff. The identity politics at that point started to rip PARC apart, really early on its evolution – like, it didn’t have much of a chance to get going. I was gone at the point. I was over in Victoria. BK: Initially, these ASOs were essentially gay men’s organizations, and now you have this new population coming in that have very different needs. I imagine it caused all sorts of tension. EA: And practical differences too. Like, a lot of gay men at the time were well-mannered and polite and – not to put too fine a point on it but white middle-class men. They were raised that way, they knew how to behave in ways that were predictable and acceptable to the institutions that grew up around to support them. And then when new people came in with different life skills and backgrounds that had nothing to do with what these service providers were used to, it “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) was a real challenge. And in my case, I know that I was very clear when I moved to Victoria that I had very little interest with dealing with that population. I didn’t know them, they weren’t my people – I’d do my work, but it wasn’t the reason I was there, and I didn’t apologize for that at the time, and I still don’t. Certainly, ASOs have evolved to meet that need, but it wasn’t my need, and that’s okay. BK: One of the other things that I have the impression might have been happening during this time within ASOs is this professionalization. Were you witnessing that shift from being – they were still volunteer-driven organizations, but bringing on a lot more staff members? EA: Yeah, like AV for example grew from an executive director with – back when we were in this sort of back alley somewhere – I don’t even remember… It was a small little office. There was an executive director and I think a part-time volunteer coordinator and that was it – everyone else was volunteer. When we moved into the PARC building, we expanded rapidly, so there were directors of everything, and we wound up from two staff, I think, when I first got involved, to twenty, twenty-five, thirty staff by the time I left, which is rapid growth over a period of a few years. Mostly, grad students, like yourself… BK: Like you at the time. EA: And yeah, they were reasonably well-paying careers. And when I moved to AIDS Vancouver, actually – this speaks to the professionalization – I was hired on contract without being told by the executive director and board that had hired me that they were in the process of unionizing, so I landed in this place, and boom, I was part of a union without my foreknowledge, and I wasn’t a particular fan of that process in non-profits, and as someone who’s the GM of a non-profit now, I’m still not a fan of unions in non-profits. BK: When you moved back to Victoria, was there still that personal involvement at the same time, or was it more professional only at that point, or institutional or organizational? EA: It was still personal. I still had friends who were affected. The care and treatment of people who were affected was becoming more sophisticated at that point. The prognoses were better for the most part. Again, there was still intolerance, and there were strange side effects like lipodystrophy and all those other things. People were disfigured, emaciated in those classic ways where people with HIV were immediately recognizable, to certainly people that knew – it was like a tattoo, you couldn’t get away from it. People were going in for cosmetic surgery to deal with it. I was dealing mostly with friends and colleagues who had HIV and were living with it as colleagues, as professional colleagues with whom I worked on a daily basis, including at the federal level, provincial, and at the local level. So, I would say a significant portion of the people who I was working with had HIV – if you had to put a number on it, maybe 20%. BK: What was it like being at an ASO, working at an ASO, as that shift occurred, as treatments started to emerge that were not without side effects but were actually effective in some respects. EA: It was exciting, it was nice – nice, that’s such a bad word. It was inspiring. It was exhilarating to feel like the medical community was starting to get traction. But that exhilaration “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) or that hope, that optimism was happening at the sort of bird’s eye level, certainly in my case anyway, because I was in the industry if you want to call it that. From a bird’s eye perspective, progress was being made. At the local perspective, the level of the individual, it was still so hit and miss that you had to make a kind of disconnect between your optimism and the direct lived experience of the person in front of you, which had very little to do with this sense of excitement, so it was an odd kind of double vision that was going on during that period. BK: When did that optimism start to feel to some extent it was being filled? EA: That was HAART – highly-active retroviral therapy, whatever it’s called – once the HAART stuff kicked in, now the bird’s eye view and the local experience of an individual are starting to meet up and we can get excited for individuals now. Prior to that, it was like pregnancy – you don’t want to jinx it. You don’t want to say to somebody, “Oh my god, I’m so glad you’re pregnant,” because it’s like what if it’s not successful? You had to be really careful and tactful about it. Once the HAART stuff started getting traction and there was this sense like, oh my god, it’s working, then you could extend the optimism that you saw in the big picture to the person in front of you, and that was awesome. BK: That must have been amazing. EA: It was. BK: It sounds like in some respects the epidemic changed your relationship to the community. EA: Well, it did. I went through a period – my response to the first inklings of the disease amplified my original impression of the gay community as dysfunctional and addicted to behaviours that weren’t productive, modelling the outcomes predicted by Larry Kramer, and that was writ large for me all over the place, and I shut down. Later on, I felt a sense quite honestly of survivor guilt through graduate school as I realized I was living in Vancouver, which was early on and deeply affected by HIV. I felt a need to contribute because I had survived. Remember, I was misdiagnosed very young – not misdiagnosed, this incompetent professional made the wrong suggestions, and that affected me for much of my early adult life. Once I got involved in HIV, I kind of got to see men and women operating at a level that reminded me of my childhood exposure to the women’s community, and that was exciting and gratifying to see, and I felt good about being a part of it. And then later, that moment in time where this mobilization around social justice, around gender, sexuality, the terror of illness and the unknown – once that moved into much more complex social issues of poverty, substance use, all of these other really complex things, I moved away once again a little bit, out of choice at that point. BK: It does sound like quite a stark juxtaposition, that first glimpse of the gay community as very hedonistic, and then this glimpse of the gay community and AIDS service organizations as very caring and human. I can see why that would have led to a shift in your relationship to the gay community. EA: Yeah, but at least I got a number of years of feeling really proud of the accomplishments of my comrades and fellow gay men under incredible duress – it was a kind of war. And gay men “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) have never had it easy – sailing through life – at least white, middle-class Canadian life, sailing through life through a kind of prescribed set of doors. You go from youth to adulthood, you go to college – like, all of these things that just kind of happen without the need to painstakingly observe your own position within it is something that gay men have to do anyway, because they view themselves as actors and as objects by virtue of their position in society. So, the idea that they also had to fight society at large, not just at the level of their own lack of privacy, because as a gay man, being out as a gay man back then – I don’t know about now but it was an act of courage, because people speculated about your private life, and you were up for public consumption, which is something that straight people rarely ever experience, except for women maybe because they see themselves as objects too. I got to be proud of my role and, more importantly, the role of my comrades in standing up and fighting for something that they believed in, and that’s a privilege that people who’ve gone to war, certainly, they’re deeply moved by that sense of comradery that they shared with their peers as well. So, I’m grateful for that. BK: And it was like going through a war in a lot of ways, from what we’ve heard from other people. It’s an apt analogy. One thing I haven’t asked about at all is just around how the government was responding. Do you have any thoughts on how that was playing out at the time? EA: Well, I was aware of – I mean, certainly, in my role, I was highly aware of – I was the one preparing the grants for AV on behalf of my directors, just because I was a good writer, so I ended up compiling the grants and so on, and writing them in some cases. The federal government was highly responsive, and they were funding AIDS in a way that was – it was excellent, because they certainly didn’t have to. Policy is blind to, or was back then – policy was blind to the vagaries of public opinion, which is the way it should be. So, back then, it was functioning in that way. Provincially, it was much more politically volatile – up and down and up and down depending on whether it was Socred, or whatever it was called, Liberal – they changed their names, the right-wing, all the time. The left-wing was pretty consistent. But it depended on who was in government. But generally speaking, ASOs had money – I mean, we raised a lot of money too for direct care, but governments were certainly on-board. I didn’t get the sense that they were the enemy. The enemy was your neighbours, not the people at the tables of government. BK: How do you think the epidemic changed the gay community besides what we’ve already talked about? EA: Well, it depends on what period of time you’re looking at, because the gay communities vacillated. Again, if you talk about the devolution of PARC, the gay community mobilized in the early years of HIV, and then was compromised by all kinds of identity politics as our response to HIV became complicated by who was living with it. So, that’s all I can say. It was just – there’s not much left of it from my perspective, but then I’m not exposed to that world anymore, I’ve drifted away. I’m too busy doing other things. BK: And how has your perspective on HIV changed, looking toward the present? “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) EA: Well, it’s a terrible tragedy that happened, but it’s a terrible tragedy in league and in competition with all kinds of other tragedies in retrospect. It was distinguished by the fact that it was embedded in stigma, right from the get-go, so that’s the big difference. Like, people are dying of starvation, they’re compromised by virtue of where they grew up – there’s all kinds of things going on in the world, but HIV was unique in that it challenged governments, societies, neighbourhoods in ways that nothing else had in my experience, except for maybe the McCarthy era in the U.S., the Vietnam War, for example. But it forced people to take a stand. Regardless of where you stood, you weren’t going to just sit down – you stood up and paid attention. I’ve lost track – what was the question? BK: Just around how your perspective on HIV has changed. EA: Okay. I mean, now it’s kind of – I think I wrote this somewhere to a friend of mine recently, that HIV, if it were a door on a street – you’re walking down the street and there’s all these doors for different things – HIV now has to compete with every other door in town. It’s got a glass front with an aluminum bar, just like every other door, and that’s just the way it is. So, the whole approach to it and the experience of it has become part of the realm of the everyday, and maybe that’s okay. Certainly, the introduction of HIV into our world caused all kinds of benefits – rapid advancements in medicine and research, not just clinical research and pharmaceutical research, but qualitative research – there’s all kinds of things, benefits that have spun off… That maybe all the people who died terrified at the beginning of the disease, if there’s any poetic justice in any of that, it’s that they contributed – those terrified deaths, those are the ones that bother me the most, the fact that that first wave of HIV died in abject terror, and a lot of times, in isolation. That’s what mobilized me as a young man who survived, and I still look back on that and I’m glad that the world has benefitted because of that. We’ll see the next time something similar happens again whether we behave any differently. [Laughs] BK: One would hope. EA: Yeah, I don’t know. BK: I think I’ve covered most of what I wanted to ask you. We always like to ask near the end, just because we are trying to think intergenerationally, whether you have any lessons you’d like to share with younger gay men today who didn’t live through this, who didn’t witness this. Any messages or wisdom you’d like to impart? EA: Um… I guess I’m turning fifty-seven the day after tomorrow – I’m not a real birthday person, but it’s a milestone of some kind. I manage a hard-working, dynamic group of about fifty to sixty employees. Most of them are between the ages of sixteen and twenty-two. In my world, they’re athletes for the most part, so they’re on-water athletes. They’re a mix of straight, for the most part, gay – HIV isn’t something that is part of their world or vocabulary – I don’t think it occurs to any of them. It might – it doesn’t come up in discussion. But what does come up on a regular basis is a sense of community and fair play, and a general sense of optimism and acceptance that goes on between all of these young people that I work with that doesn’t seem to stigmatize people beyond a sense of humour, whether you’re gay or straight – I mean, we don’t have any transgender staff that I know of, I don’t think we do. Things have moved forward, and I “HIV in My Day,” Erik Ages (April 17, 2019) think that for gay men in particular, I’m reminded of the Jews who honour the people they’ve lost to the Second World War, and the steps subsequent to the Second World War, and the actual people who fought in the Second World War to give us the life that we have today. We owe – including me – we owe all those people a sense of duty. God, I’m getting emotional. It’s good to honour those people. Anyway, this doesn’t come up with all of the young people that I deal with, but the very fact that I’m a gay man, publicly, looking after all of these exuberant young people is a signal of progress that – it’s not about me, it’s about the fact that people demonstrated courage, and it wasn’t an easy thing for them to do. God, I have vivid memories of the fear – I can’t get over it. Anyway, that’s what I would say. I can’t believe I’m emotional. It’s okay… [Long pause] Okay, I’m better now. [Laughs] BK: But to remember, that’s what it comes down to in a lot of ways. To acknowledge and remember. EA: Yeah, and for young people who are dealing with isolation, because I don’t delude myself, I think that being gay and young is still isolating. You may have apps and Porn Hub and whatever it is that people are using these days that give you a sense of community. I feel like I’m returning back to when I was a teenager going to these bars, so Porn Hub is today’s gay bar, essentially. I would urge young people to look beyond the gay community for role models and be their own role model, and integrate with the community at large, and just be proud of who you are – you don’t need to be stitched together with a community just by virtue of your sexual choice, which is a victory, and that is the one significant victory out of all of this, that you can be a leader or look to leaders not just because of who you sleep with. Nevertheless, if you are isolated, if these young folks are isolated, take steps to stop that from happening to yourself. BK: Find a community, whatever that looks like. EA: Yeah, whatever that looks like. Yeah. BK: Well, that’s it for my formal questions. We always like to leave some time at the end just to ask if you have anything you wanted to add or anything we covered in passing that you wanted to expand upon. EA: Nope. It was good. BK: Thank you, Erik. EA: I surprised myself. BK: I’ll stop this if you have had your say.

An interview with Erik Ages as part of the HIV in My Day Oral History project. Interviewer: Ben Klassen. Location: Victoria.

- In Collection:

- 00:07:48 (Part 01)

- 01:07:04 (Part 02)

- 48.4359, -123.35155

- HIV in My Day

- YouthCO HIV & Hep C Society

- Lachowsky, Nathan

- Vancover Island Persons Living with HIV/AIDS Society

- Rights

- This item made available for research and private study. For all other uses please contact Dr. Nathan Lachowsky.

- DOI

| Thumbnail | Title | Date Uploaded | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Interview with Erik Ages Part 01 | 2021-05-28 | |

|

Interview with Erik Ages Part 02 | 2021-05-28 | |

|

|

Interview with Erik Ages transcript | 2021-05-28 |